This post is meant as a resource page for a talk I gave at EBASCON 2017 in Munich. I will include links to sources and other posts which expand on the points made in my presentation. The links include articles on Skybrary.aero, an excellent resource curated by Eurocontrol about all kinds of Safety relevant information, and previous blog articles of myself which expand the idea. Over time, I hope to produce a video to recap the presentation which I will publish here too.

This post is meant as a resource page for a talk I gave at EBASCON 2017 in Munich. I will include links to sources and other posts which expand on the points made in my presentation. The links include articles on Skybrary.aero, an excellent resource curated by Eurocontrol about all kinds of Safety relevant information, and previous blog articles of myself which expand the idea. Over time, I hope to produce a video to recap the presentation which I will publish here too.

If we look at the development in Safety Management Systems in aviation, we see that most organisations have built capable systems to capture safety data from their organisation.

I helped organisations across the globe with implementing SMS, for many it was not easy to set it up all these tools ( the reporting systems, investigations, LOSA, …), but it is an even steeper learning curve to use that data in a way that contributes to a better/ safer performing operation.

All too often SMS has become like exercise equipment on television; a lot of promises that this latest gadget will solve your problem. Even many Safety seminars had this message that “the safety data will set you free!”.

The underlying thought that a more data oriented approach to managing safety will be more effective, is not wrong in itself. However, the assumption that having the best tool for gathering safety data will automatically lead to the best safety decision making is suspect: we have to remain critical what this SMS is actually producing!

Just having a good tool is not a guarantee that you will do a good job with it.

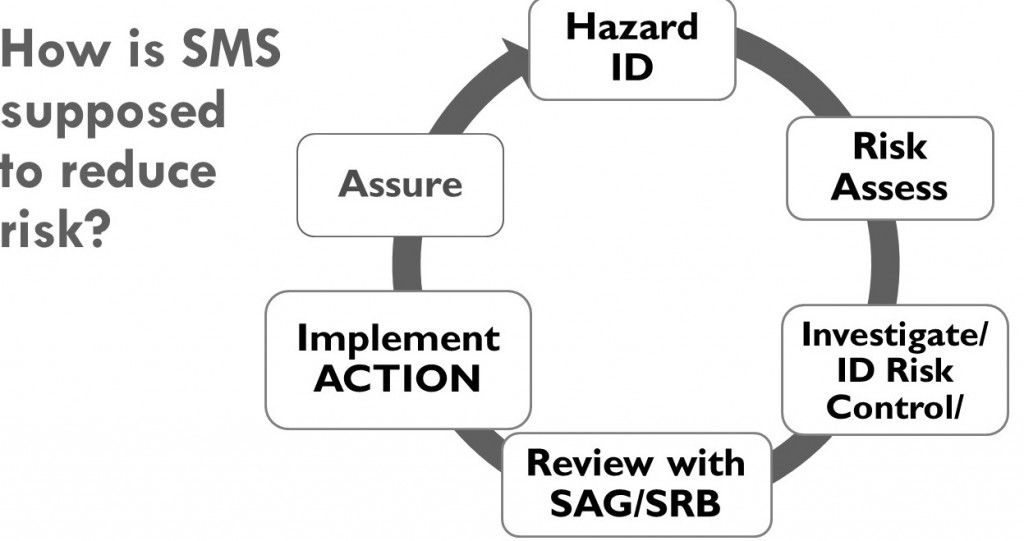

In the race to implement SMS to achieve the implementation deadline it seems that the industry has lost sight why it was important to have an SMS. The idea was that through the SMS we could do better Safety Risk Management.

Many organisations are not integrating the SMS output in the decisionmaking of the company, with a lack of improvement in Safety Performance as a result.

It is not the exercise bike’s fault if you are not getting in shape! Neither is the SMS necessarily to blame if it is not used to do something about risk.

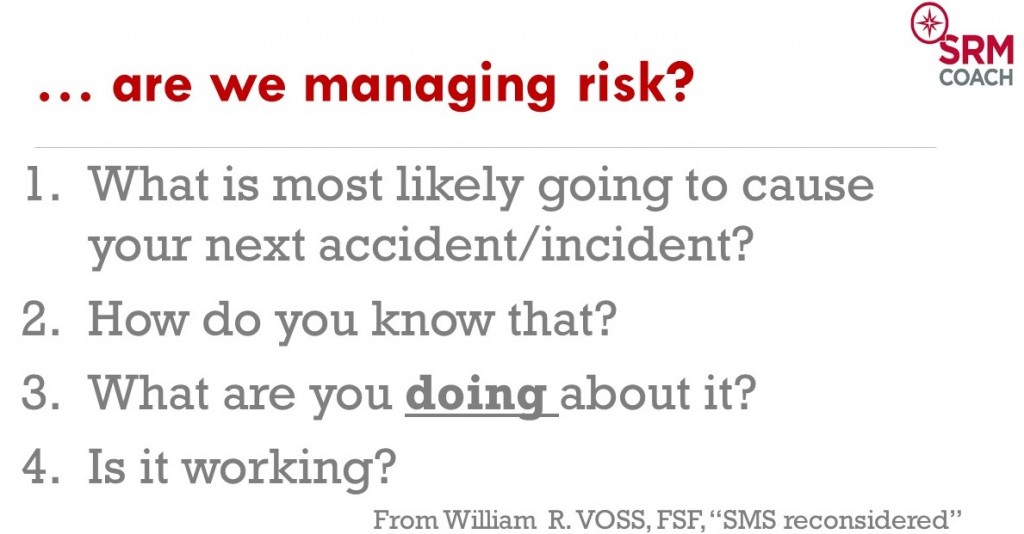

Or as Bill Voss from the Flight Safety Foundation described it in his article SMS reconsidered : “The whole purpose of having an SMS is to be able to better allocate resources to reduce risk” ; safety risk management or risk based decision making if you will.

Or as Bill Voss from the Flight Safety Foundation described it in his article SMS reconsidered : “The whole purpose of having an SMS is to be able to better allocate resources to reduce risk” ; safety risk management or risk based decision making if you will.

To evaluate if your organisation is doing that, Bill Voss gives 4 simple but powerful questions to evaluate your department or organisation:

I have been asking variations of these questions all over the world in organisations which have an SMS already. Even in pretty sophisticated organisations with a great attitude towards SMS implementation, few people have convincing replies to these 4 questions.

If there are any replies at all, you get pretty different viewpoints between those of the senior management and people on the work floor. From that experience, I have to agree with Bill Voss; it seems that many organisations have missed the point of having an SMS completely. As often happens in aviation, it became a compliance driven exercise, doing it because it is mandatory.

A lot of organisations in aviation might now wrongly assume the SMS work is now “done” because they have passed previous audits where they showed they have the elements of the SMS as asked for in the ICAO manual.

But audits from authorities are evolving! Most Civil Aviation Authorities will take their cue from the Safety Management International Collaboration group.

From their SMS evaluation tool you can see that indeed, initially the SMS was evaluated to see if it is “present and suitable” for the organisation.

Basically they were checking that all the processes, databases, policies etc were there.

That phase is over now, the bar has been raised! The next phase will shift focus to what the SMS is producing, is it operating and effective?

The implication of this is that your regulator can shift to performance based oversight.

Basically this means that in those organisations where it is demonstrated that the SMS is effective and generating positive results in reducing operational risk, frequency of audits will be able to decrease. While those organisations which cannot demonstrate an operating and effective SMS will receive closer and more frequent oversight.

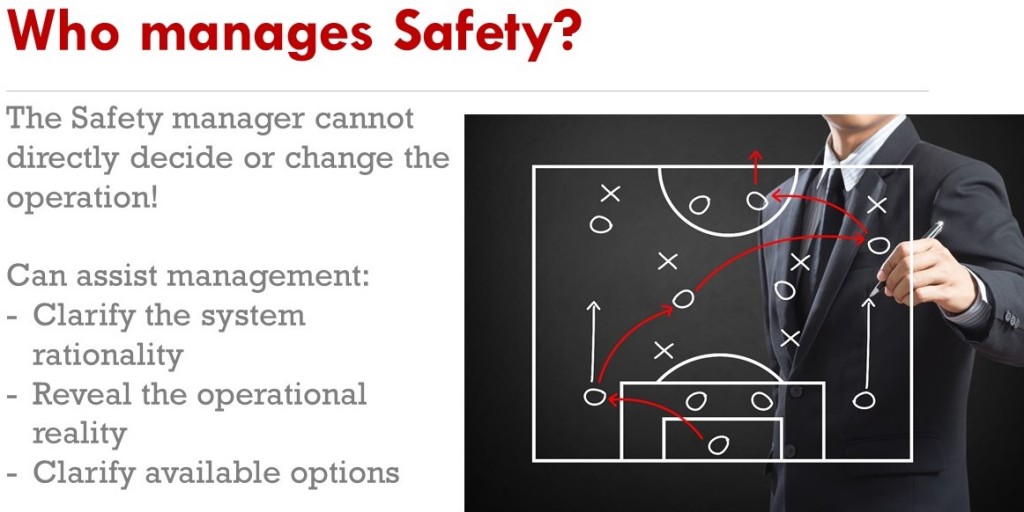

There is still confusion between the Safety Management System and Safety Management. In the picture here you see a simple safety Management cycle, with the first 3 (Hazard ID, Risk Assessment, and investigation) and half of the 4th (Safety Action Group and Safety Review Board) under control of the “Safety” Manager, these activities are part of the SMS. But the 5th box “implement Action” firmly remains with the management team though! Despite the misleading title, the Safety manager does not manage safety at all, the only thing they manage is the SMS itself, the output of which goes to the management team, and in the end it is their decision-making and most of all their actions in implementing safety recommendations that will improve Safety Performance of the operation. I explain this in another article at length here.

There is still confusion between the Safety Management System and Safety Management. In the picture here you see a simple safety Management cycle, with the first 3 (Hazard ID, Risk Assessment, and investigation) and half of the 4th (Safety Action Group and Safety Review Board) under control of the “Safety” Manager, these activities are part of the SMS. But the 5th box “implement Action” firmly remains with the management team though! Despite the misleading title, the Safety manager does not manage safety at all, the only thing they manage is the SMS itself, the output of which goes to the management team, and in the end it is their decision-making and most of all their actions in implementing safety recommendations that will improve Safety Performance of the operation. I explain this in another article at length here.

The role of the Safety Manager is rather similar to that of a coach, in that they cannot actively play on the field, but can only provide overview and advice to the team. If you think about it, the Safety Manager does not have direct influence in the operation, does not have the authority to make decisions or implement actions and does not have a budget other than to run the SMS.

Much like the finance director and financial performance, the Safety Manager provides the management team with advice, and the resulting actions (or lack thereof) from the management team will impact the safety/finance performance of the organisation. But the Safety Manager can help the management team make better informed decisions to reduce risk in the operation.

So it is important to separate the tool from the activity, the SMS is a tool to achieve better Safety Management, which is inseparable from the overall management of the company. Any decision made by a manager will have some financial, comercial, operational, safety, quality, reputational impact. As Gerard Forlin said in his excellent speech, you can’t separate out Safety.

For the purposes of this presentation I´d like to highlight 3 main problem areas in SMS and Safety Management which come up a lot.

For the purposes of this presentation I´d like to highlight 3 main problem areas in SMS and Safety Management which come up a lot.

In part 1 I will talk about how our mindset to troubleshoot complicated systems (like our aircraft, engines etc.) is not always useful to troubleshoot complex systems (our organisation). The mix up between these two mindsets is responsible for a lot of misunderstanding and ultimately misguided attempts to reduce risk.

In Part 2, I will highlight how the reality of operations sometimes is oversimplified and I discuss a freely available toolkit that can be applied to explain failure in our complex systems better, with hopefully more effective safety interventions as a result.

In part 3 I talk about some strategies that can help to generate constructive action in your organisation, using well proven coaching principles.

Understanding Risk in complex systems

First of all I think it is very important to talk about complexity! The ICAO SMM itself recognises that the aviation system is a complex system and we need to understand how the multiple and interrelated components impact human performance. (That is what Human Factors really is, the study of human performance). Our normal “technical” mindset we use very successfully to solve problems in complicated systems, does not necessarily generate good results when trying to solve problems in complex systems.

First of all I think it is very important to talk about complexity! The ICAO SMM itself recognises that the aviation system is a complex system and we need to understand how the multiple and interrelated components impact human performance. (That is what Human Factors really is, the study of human performance). Our normal “technical” mindset we use very successfully to solve problems in complicated systems, does not necessarily generate good results when trying to solve problems in complex systems.

Let’s define a complicated system:

Complicated systems

Complicated systems are often called complex, but this is usually incorrect:

E.g. an aircraft engine, which most people describe as ‘complex’ is actually an ordered, decomposable and predictable system.

When applying systems thinking, something like an aircraft engine is a complicated system which can be described by these properties:

- it can have many interacting parts,

- the interactions are usually known and predicable and are linear (a certain input has a certain output)

- there is one optimal operation method, the system can fail when deviating too far from this method

- failure of complicated systems is usually due to a component

As technically minded people, we are most familiar with complicated technical systems, which is usually what attracted us to work in aviation in the first place. Technology in aviation is the most complicated and challenging to master and it gives a special sense of satisfaction to be able to figure it out.

It is possible to “know” the entire system, in the sense that we can model what will happen in any circumstance, even when a bird will go into the engine, we can with great confidence know what will happen.

So like our cars (a complicated system) there are many parts, and provided we remain within the optimal operation method (rpm´s , speed, etc.) we should not damage it. If the car stops working, the way to identify the failure is simple, look at the individual components, find the faulty one and replace or fix it and the complicated system works again. As technical people this is what we are familiar with, and when we look at our organisations we tend to equate them with machines. But there are fundamental differences that we have to be aware of!

If the car stops working, the way to identify the failure is simple, look at the individual components, find the faulty one and replace or fix it and the complicated system works again. As technical people this is what we are familiar with, and when we look at our organisations we tend to equate them with machines. But there are fundamental differences that we have to be aware of!

Implications of complicated systems:

- In complicated systems we obtain the solution through analysis, reducing the system to a view of its components. This is the traditional “scientific method” which we as technical people are most familiar with.

- Troubleshooting a complicated system after failure is usually quite straightforward; investigate and identify broken components, fix these component and the system should work again.

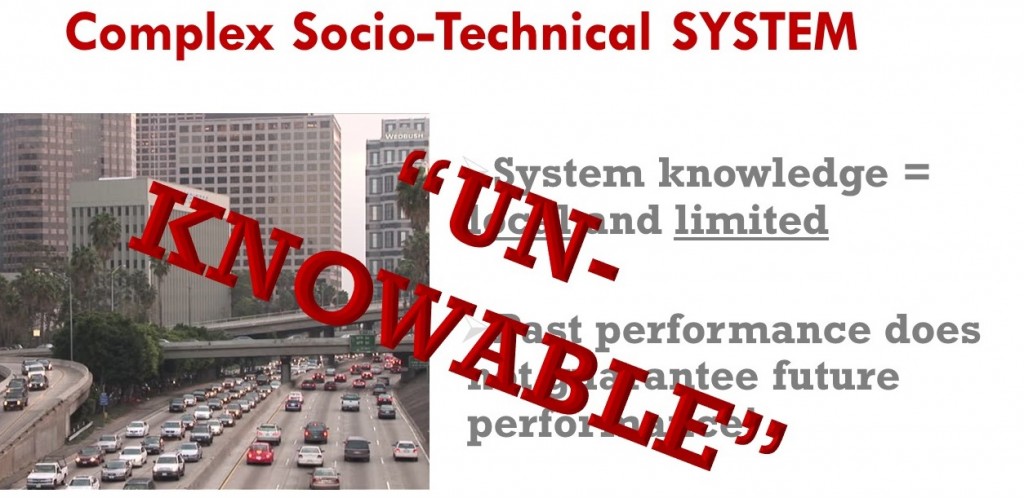

An example of a complex-socio technical system is traffic: we take a lot of complicated systems (cars, roads, traffic lights) and add them to lots of humans, now our system is very different from a complicated one! The following properties of complex systems might literally make your brain hurt!

A business is a combination of various elements like e.g. raw materials, technology, people and infrastructure, which work together to perform a function.

In the case of an airline that function is to transport people from A to B (hopefully profitably). To perform that function there are many daily interactions necessary between an ever varying multitude of actors in the system:

Pilots, cabin crew, assistants, engineers, supervisors, managers, and support staff routinely interact with each other and with others such as ground staff, ATC controllers, 3rd party contractors, drivers and airport staff.

People interact with various types of equipment (Flight planning software, weather radar, aircraft, ground equipment,…) with much information (EFIS, manuals, flight plans, NOTAMS,…) regulations and with many procedures.

These interactions are always different and unpredictable. Further increasing the dynamic nature of interactions in the aviation system are the various external factors such as weather, terrain, time schedules, maintenance issues, manpower, other traffic, conflicting or lacking information and other resource constraints,…

Implications of complex systems:

- In a complex system there are many dynamically interacting components, people AND systems, there is almost never an identical combination of these elements and external factors.

- Nobody can fully understand the whole system, everybody in the system has a limited view and knowledge of what is going on. Knowledge of the complex system is always limited and local!

- Like the stock market; past performance does not predict future performance! So the fact that you did not have any accidents in the past, does not guarantee you will have no accident in the future.

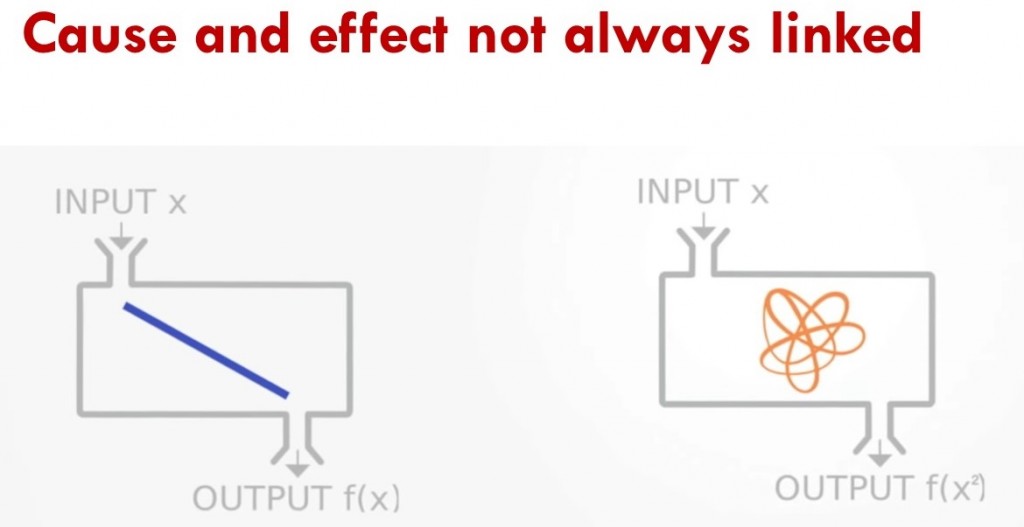

In complex systems, non-linear behaviour occurs which mean that small inputs can create huge outputs. E.g. traffic jams, one car braking briefly can generate a traffic jam 5 km downstream.A complex system can fail without a component breaking! Due to unplanned/ unforeseen interactions everyone can follow the rules but still an accident can happen.

In complex systems, non-linear behaviour occurs which mean that small inputs can create huge outputs. E.g. traffic jams, one car braking briefly can generate a traffic jam 5 km downstream.A complex system can fail without a component breaking! Due to unplanned/ unforeseen interactions everyone can follow the rules but still an accident can happen. We cannot observe the function of a complex system just by looking at the individual components. We need to see how the various ways the elements can interact and relate to each other.This plays at another level too, when we are looking at the behaviour in and of the system.

We cannot observe the function of a complex system just by looking at the individual components. We need to see how the various ways the elements can interact and relate to each other.This plays at another level too, when we are looking at the behaviour in and of the system.

Behaviour is emergent, or rather a result of system conditions, the actors in the system don´t necessarily choose to behave in a certain way. “Emergence means that simple entities, because of their interaction, cross adaptation and cumulative change, can produce far more complex behaviours as a collective and produce effects across scale.” System behaviour therefore cannot be deduced from component-level behaviour and is often not as expected. For instance the movement of a flock of birds is a result of the cumulative behaviour of all the individual birds which follow three simple rules

1) Maintain separation from your neighbours

2) follow the average heading of your neighbours

3) follow the average heading of the flock.

In complex systems, non-linear behaviour occurs which mean that small inputs can create huge outputs. One illustration of this is the so-called butterfly effect in weather predictions, a small difference in initial conditions which can contribute to a wholly different outcome.

In complex systems, non-linear behaviour occurs which mean that small inputs can create huge outputs. One illustration of this is the so-called butterfly effect in weather predictions, a small difference in initial conditions which can contribute to a wholly different outcome.

This often difficult for our brain to understand, we like to think about the world as nicely linear and Newtonian, an effect can be linked directly to a cause. Sometimes there is no direct causal factor! (the butterfly in Brazil actually in this thought experiment does not “cause” the tornado, it only contributes to a difference in initial conditions from which one result could be the Tornado in Texas (, like I said difficult for your brain to grasp…)

Consequences of “complicated” corrective actions in complex systems

From Skybrary:

Treating a complex socio-technical system as if it were a complicated machine, and ignoring the rapidly changing world, can distort the system in several ways.

First, it focuses attention on the performance of components (staff, departments, etc.), and not the performance of the system as a whole. We tend to settle for fragmented data that are easy to collect.

Second, a mechanical perspective encourages internal competition, gaming, and blaming. Purposeful components (e.g. departments) compete against other components, ‘game the system’ and compete against the common purpose. When things go wrong, people retreat into their roles, and components (usually individuals) are blamed.

Third, as a consequence, this perspective takes the focus away from the customers/ service-users and their needs, which can only be addressed by an end-to-end focus.

Fourth, it makes the system more unstable, requiring larger adjustments and reactions to unwanted events rather than continual adjustments to developments.

Improving safety performance in complex socio- technical systems

A systems viewpoint means seeing the system as a purposeful whole – as holistic, and not simply as a collection of parts. We try to “optimise (or at least satisfice) the interactions involved with the integration of human, technical, information, social, political, economic and organisational components”. Improving system performance – both safety and productivity – therefore means acting on the system, as opposed to ‘managing the people’.)

This is where you see many well meaning safety efforts go off the rails: putting up posters with the message “be careful” demonstrates a total lack of knowledge about systems thinking and has as an underlying assumption that people are choosing to be unsafe in the first place and hence will to choose to be safer once they see the poster.

The problem is that our brain is not necessarily well adapted to comprehend complex systems. Our brain mainly prefers linear thinking, cause and effect etc.

This is very well explained in the work of Daniel Kahneman, a psychologist who won the Nobel prize in economics. His work can be summed up as decision making under uncertainty, which if you think about it sums up risk management nicely.

He describes in his book “Thinking, fast and slow” two modes of thought: “System 1” is fast, instinctive and emotional; “System 2” is slower, more deliberative, and more logical. We assume we are rational beings, and while we are certainly capable of rational thinking, it costs more energy.

Most of the time we use our system 1 type thinking which is good for day to day decision making because it is mostly going on pattern recognition from previous situations. (That’s how you got home in your car without remembering actually driving).

In complex systems however, we have to be careful however, our brain has a lot of biases and heuristics which can make our judgement flawed. The result is that more often than not we can jump to the wrong conclusions if we do not look at the problem in a systemic manner. Very often we find that very complex operational problems are oversimplified, to absurdly simple concepts.

The second part of this talk is about how many organisation have a flawed picture of their operational reality, the SMS is supposed to hold a mirror up to the organisation, but often reality is not reflected accurately. (“We don’t have any reports so nothing is wrong!”)

Human Factors refers to the study of human capabilities and limitations. It’s aimed at optimising human performance in the workplace.

Many of our risk controls depend on rules, regulations and procedures. However in real life it is not always possible to follow this “ideal way of doing things”. From a risk perspective, if we assume that the procedures and regulations are part of our risk controls, people can actually potentially increase the likelihood of an accident by not complying. So why do people not follow procedures and regulations?

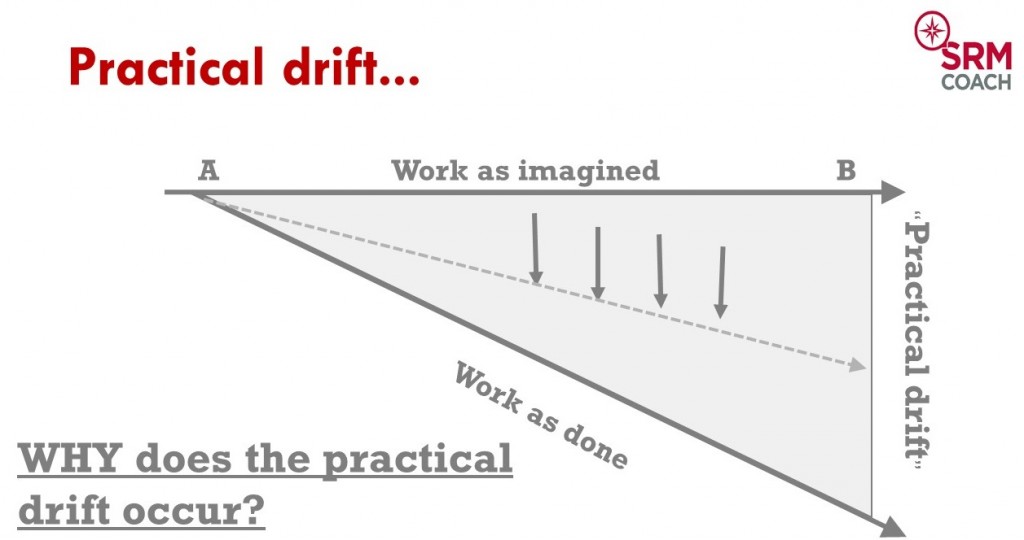

There are several issues impacting this view of operational reality, First of which the concept of practical drift :

ICAO defines practical drift as when “…operational performance is different from baseline performance.” Baseline performance is the performance expected upon initial deployment of the system and is based on three assumptions:

- The technology needed to achieve the system production goals

- The training necessary for people to properly operate the technology

- The regulations and procedures that dictate system and people behaviou.

Practical drift can also be expressed as the difference between “work as imagined” and “work as done”

The work as we imagine it to be done is what we describe in our manuals and procedures, it is an idealised version of how it should be done.

However in day-to-day operations, the way work is actually done, drifts away from this “ideal” way to do things.

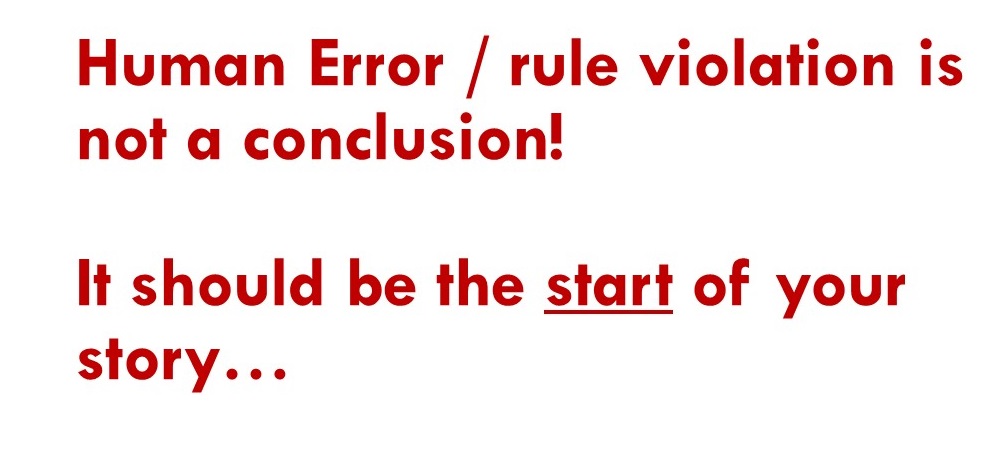

We can distinguish 2 major reasons why people deviate from our “work as imagined” line, which in effect means they perform “unsafe acts”.

– Human Error: humans are not perfect and will make involuntary errors and mistakes, many times performance influencing factors provoke error

– Violations: Persons sometimes consciously choose to violate procedures and regulations

Most of the time, at this point in the explanation of practical drift, the argument is people should simply follow the rules”, and hence the view of compliance based safety, the situation is sometimes absurdly simplified to, “the rule was broken, hence an accident followed”.

In fact, in day-to-day operations, rules are broken all the time, because of a variety of reasons, some indeed linked to “optimisation” but in some cases because it simply is not feasible to follow all the rules and get the job done. (Described by Erik Hollnagel as the ETTO principle or Efficiency-Throughness-Trade-Off: You can either follow all the rules or be as fast as possible (Efficient) and people have to constantly trade off between the 2).

When nothing goes wrong nobody asks questions, (e.g. Have an AOG with a 3 hour maintenance action and a slot in 1,5 hours, Wanna bet the aircraft is going to be fixed in time? And if the aircraft is fixed on time to make the slot, are we angry at the engineer for rushing ? )

Another example that shows a bit of hypocrisy going on in the industry is the work-to-rule strike. In occupations not allowed to strike, like ATC, they will follow every rule in the book and everything goes slower. Think about that for a minute, isn’t that what they are supposed to do all the time, follow all the rules? What are they doing when everything is going well? (Efficient)

So rather than blindly insist that everyone should just comply with the rules, we need to understand first WHY the practical drift is occurring! Do the rules still make sense, maybe on an individual basis yes but if we take them as a whole we see that there are many incompatibilities and conflicts that have grown over time.

This is why we need to understand complexity and the concept of local rationality, before we can formulate effective safety recommendations.

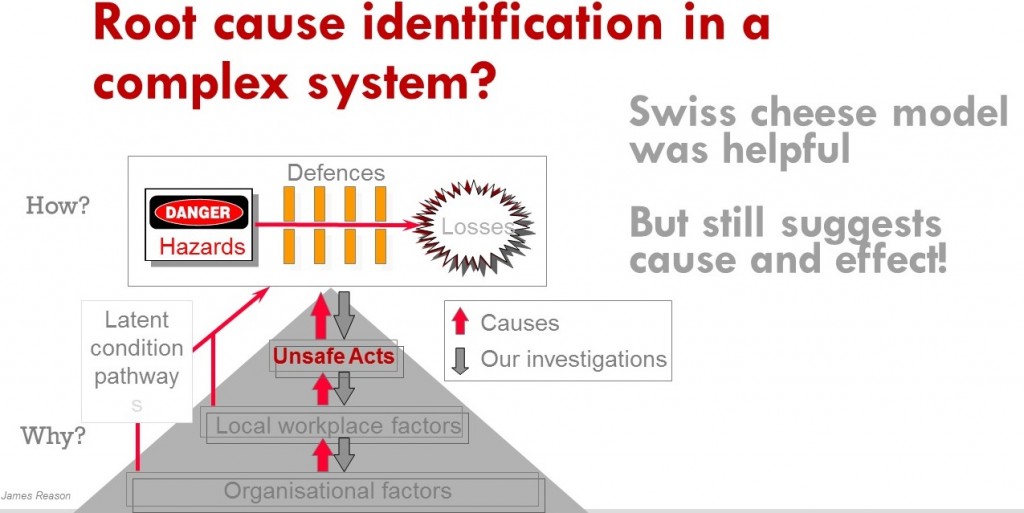

When an accident happens we are quick to try to build a story from the available information. Basically looking for a cause and effect type story (system 1 in action). We try to make sense of what happened.Let’s illustrate this with a fictional example:

When an accident happens we are quick to try to build a story from the available information. Basically looking for a cause and effect type story (system 1 in action). We try to make sense of what happened.Let’s illustrate this with a fictional example:

E.g. Helicopter made a hard landing in bad visibility…

Investigation (fictional):

Investigation (fictional):

Crew of a Medevac was called out on an ambulance mission. Their landing light failed, they

attempted landing, without landing light during night VFR conditions:

Result was that they misjudged the landing, made a hard landing and the gear collapsed.

During the investigation it was found out aircraft took off with 1 landing light bulb INOP. Other bulb failed during flight.

Conclusion:

“Human Error”, crew should have not accepted to take off with one bulb inop, should not have landed.

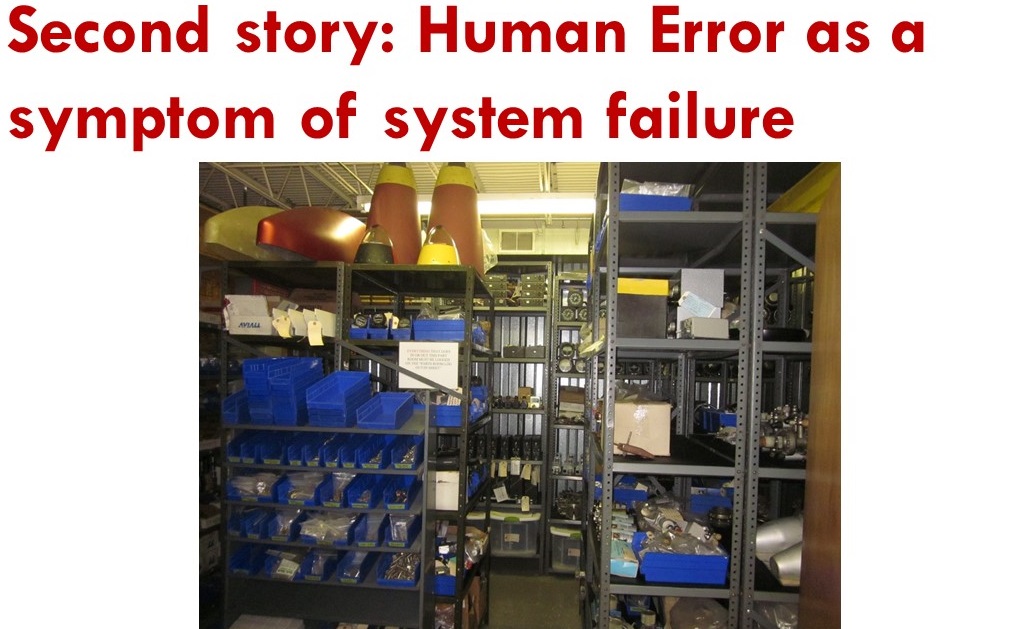

This is a typical “analysis” i.e. find the broken components (bulb + decisionmaking of pilot)

What can you fix if you go on the bases of this kind of story? Replace broken components? (fix bulbs + replace pilot)

How does this conclusion help you? Will it prevent the next accident?

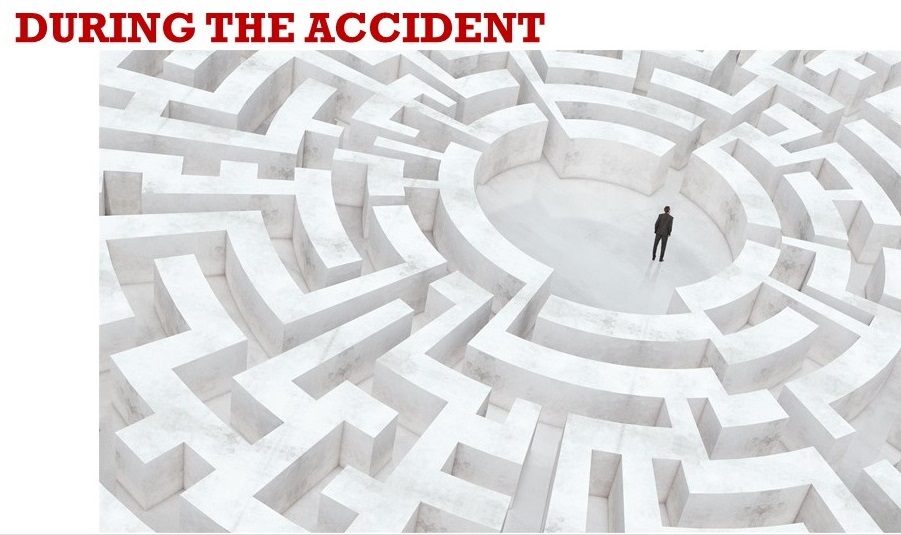

Our thinking is focussed on finding the “one” decision which set in motion the whole sequence of events, much like in Back to the future. “If we could only reverse that decision, the accident would not have happened…”

What we are really doing is oversimplifying the situation to find a satisfying narrative that makes sense to our simple brain, simple cause and effect. No accident investigation can contain all the details so, knowing what happened we simplify the story from something that looked like this to the person during the accident sequence:

To something like this:

To something like this:

This is really what hindsight bias is all about: after knowing what happened, we make up this simplified narrative in our head which we pretend to be the situation when it happened. So we call the individual in the situation “stupid” for making a mistake that seems so obvious. That is the whole problem with biases, even knowing that you have it does not change your judgement. This kind of thinking is inevitable and automatic. To protect ourselves against these overly simplistic explanations of safety problems, we have to design our safety Management systems to protect ourselves from these narratives. We have to build an additional second story which forces us to look at the situation in a more systemic manner at the situation.

This is really what hindsight bias is all about: after knowing what happened, we make up this simplified narrative in our head which we pretend to be the situation when it happened. So we call the individual in the situation “stupid” for making a mistake that seems so obvious. That is the whole problem with biases, even knowing that you have it does not change your judgement. This kind of thinking is inevitable and automatic. To protect ourselves against these overly simplistic explanations of safety problems, we have to design our safety Management systems to protect ourselves from these narratives. We have to build an additional second story which forces us to look at the situation in a more systemic manner at the situation.

So as a defence we have to apply Systems thinking, finding out the WHY? Obviously in our fictional scenario, you can find the wrong decisions, but what was the context of those decisions? Why were they taken?

If you dig deeper, you can find out more about the underlying issues that shaped the decisionmaking. E.g. in this case you could look at the spare parts management of the company. In an effort to “lean out” the spare parts stock, the company saved 2 million USD and the maintenance manager was very satisfied. However talking to the engineers, the result was a jump in overtime because a lot of parts needed to be cannibalised from aircraft in maintenance to keep the others flying. Another consequence was that in that organisation (offshore helicopters) there was an annual budget of 5 million USD for fines to be paid to the client because they missed punctuality targets due to lower dispatch reliability.In the same organisation, pilots casually mentioned they would take off regularly with items like inop light bulbs, because they knew the spare parts were not available anyway. This is called the normalisation of deviancy, coined by Diane Vaughan, looking into the Challenger launch decision.

“Social normalization of deviance means that people within the organization become so much accustomed to a deviant behavior that they don’t consider it as deviant, despite the fact that they far exceed their own rules for the elementary safety” [5]. People grow more accustomed to the deviant behavior the more it occurs [6] . To people outside of the organization, the activities seem deviant; however, people within the organization do not recognize the deviance because it is seen as a normal occurrence. In hindsight, people within the organization realize that their seemingly normal behavior was deviant.”

Although it sounds bad, we have to remember local rationality (explained next): to the people who are doing this there are, to them, reasons for doing it. Because it almost never goes wrong, this “deviant” behaviour is perceived as innocent. These people are not intentionally trying to be unsafe, they start to believe that what they are doing is “safe enough” because they don´t see negative consequences, until it goes spectacularly wrong of course.

So if you start to look at the wider picture surrounding this landing accident, you can see the breeding ground of the decision to dispatch. That does not mean it is an excuse, but it creates a wider understanding and more opportunities to fix the system to reduce the likelihood that similar situations could occur.

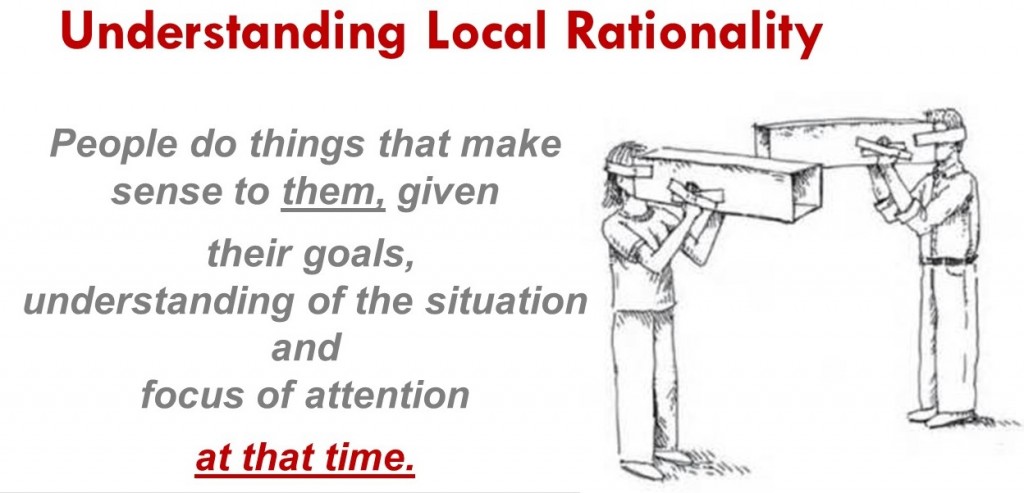

People make decisions based on their own local rationality:

Local rationality is a key systems thinking principle to understand how people in a complex system view the world: explanation can be found here

When we do something we believe that we do reasonable things given our goals, knowledge and understanding of the situation and focus of attention at a particular moment.

In most cases, if something did not make sense to us at the time, we simply would not have done it.

This is known as the ‘local rationality principle’.

Our rationality is local by default – to our mindset, knowledge, demands, goals, and context. It is also ‘bounded’ by capability and context,

limited in terms of the number of goals, the amount of information we can handle, etc.

While we tend to accept this for ourselves, we often use different criteria for everybody else!

We assume that they should have or could have acted differently – based on what we know now (the “simplified story” created through hindsight bias) .

This counterfactual reasoning is tempting and perhaps our default way of thinking after something goes wrong. But it does not help to understand performance, especially in demanding, complex and uncertain environments.

In the aftermath of unwanted events, human performance is often put under the spotlight. What might have been a few seconds is analysed over days using sophisticated tools. With access to time and information that were not available during the developing event, a completely different outside-in perspective emerges. Since something seems so obvious or wrong in hindsight, we think that this must have been the case at the time.

But our knowledge and understanding of a situation is very different with hindsight. It is the knowledge and understanding of the people in the operation, doing the work, which is relevant to understanding work.

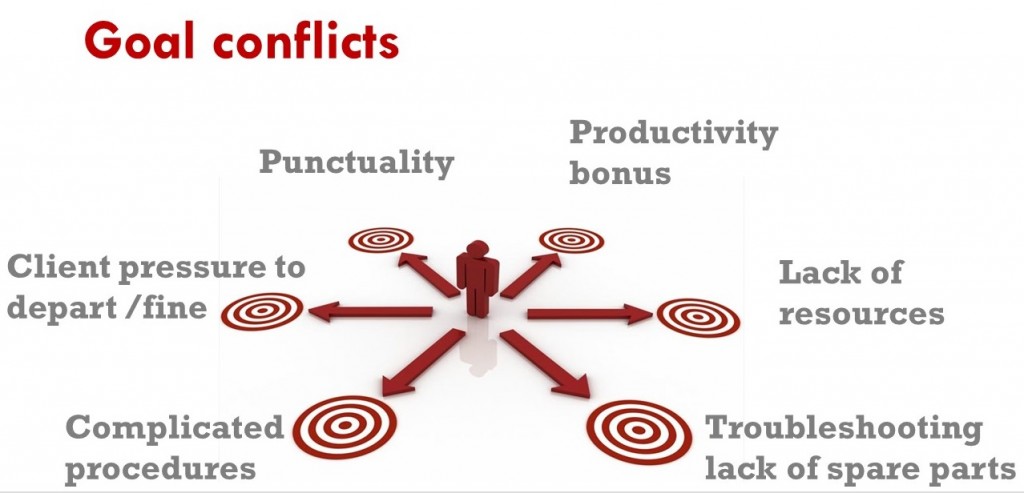

A specific property of local rationality I would like to focus on is that of goal conflicts:

Often the pretense of the concept of practical drift is that “people should just follow the rules” or be “compliant”. When things went wrong that is where the focus of the investigation tends to go to “did they follow the rules?”. But in reality there are many other goals that people need to follow to “get the job done”. If they would only worry about following all the rules in normal operations, very quickly they would be shouted at for being to slow, costing too much money, missing punctuality etc.

If you think about it, it is a wonder anything gets done at all with all these constant conflicts, if you would let a robot do the job, very soon things would grind to a halt.

As an interesting sidenote: this is exactly what happened with the first autonomous vehicles from Google: when initially programmed to follow the rules strictly, the Google cars could actually not function in traffic!

This is where the Reason model can be misleading, these factors might not immediately “cause” failure in our system, rather they shape the day-to-day decision making of our people and managers.

So rather than accepting the first “simple” story, we have to build a second story that takes into account the context of our complex socio technical system that shapes the behaviour of our people.

So rather than accepting the first “simple” story, we have to build a second story that takes into account the context of our complex socio technical system that shapes the behaviour of our people.

To enable you to do this, there is an excellent resource available on Skybrary called Toolkit:Systems Thinking for Safety: Ten Principles which I highly recommend for safety professionals to generate more effective safety recommendations, which is the absolute prerequisite for the organisation to be able to take more effective action!

To enable you to do this, there is an excellent resource available on Skybrary called Toolkit:Systems Thinking for Safety: Ten Principles which I highly recommend for safety professionals to generate more effective safety recommendations, which is the absolute prerequisite for the organisation to be able to take more effective action!

3) Taking (Effective) action to reduce risk

3) Taking (Effective) action to reduce risk

Then as a third part of the presentation I would like to highlight another problem area in Safety Management, (or any management activity really): taking effective action. As I explained in the beginning of the talk, it is one thing to know about risk in your operation, the crucial question is “What are you doing about it?”

This is very often where you can see a disconnect in many organisations, where the safety management process is missing a few steps. Very often, raw data is dumped on the table of the Safety Action group and rather than decision making, there are endless technical discussions trying to analyse what it means, etc.

A mistake often made in many organisations is to short-circuit the Safety Management cycle, directly going from safety reports to trying to decide in a safety action group.

It is a pitfall which leaves everyone wide open to shallow “System 1” type thinking because of several reasons:

1) a safety report, under the best of circumstances is a subjective, incomplete write-up or opinion by an individual of something that happened.

Because of limited and local knowledge (see complex systems) and local rationality, that one person cannot completely give all angles to the problem or level of risk. We need risk assessments to make sense of the level of priority and when necessary safety investigations to generate effective safety recommendations.

2) data overload: imagine the CFO coming to the CEO´s office and dumping a whole stack of individual expense reports. “Here is all the data, please make a decision” How fast do you think the CFO will be kicked out the CEO´s office? Yet this is exactly what some SMS´s are doing with safety data (I´ll admit, I did it too). They are not converting all this data into a risk based picture for our management team to make informed decisions!

Ideally a safety action group should be quite short:

1) “this is the safety problem and potential consequences” (Risk)

2) “This is why it happened, and these are the options to reduce that risk” (safety recommendations)

3) “Please decide what you want to do” (note that doing nothing can be a valid decision if it is justified)

The follow up SAG should then deal with the question “does it work?” demonstrating that the actions taken are :

A) implemented, timely and effectively

B) working

Another obstacle to getting to this positive decision making is that often the discussion does not deal with the crucial WIFFM “What is in it for me?” Again it comes back to the concept of local rationality. The managers in a SAG or SRB also have their own peculiar local rationality:

They have personal goals, focus of attention and understanding of the situation. And each of the managers has a different local rationality! So to be effective the safety communication needs to address their local rationality:

Address the goal conflicts and make them visible: it will be unrealistic to eliminate goal conflicts, but they have to be visible or the decisionmaking process will suffer or be ineffective. If it is not clear upfront what the tradeoff of a safety decision is, the person responsible for implementation might not implement it effectively.

I was very glad to be preceded by Gerard Forlin, QC who explained the legal side of safety gone wrong. Basically the talk illustrated very clearly is that legally the organisation and its responsible managers HAVE to deal with the risks the organisation has identified. Which if you think about it is what is expected anyway by the regulator, shareholders and customers.

A) if you know about a risk and not do something about it, you are in trouble

B) It is no excuse that you did not know about it, you ought to have known about it (ignorance is no excuse, if something happened in the industry, you are supposed to know about it)

C) Writing an e-mail to cover your backside is almost worse than not doing anything at all

So the third question “What are you doing about it?” is vital; Are your actions going to be credible to reduce the risk to an acceptable level. In many organisations, this “doing” is confounded with writing an e-mail or sending yet another instruction to staff. The infamous quick fix:

These kinds of “fixes” are often born from “system 1” type thinking and miss the Systems Thinking angle.

They are the equivalent of “be careful” posters or e-mails. the underlying assumption seems to be that people chose out of their own free will to behave unsafely, forgetting that in complex systems behaviour is emergent, a result rather than a cause.

Publishing yet another email is not action, and neither is it going to be effective. All these superficial “quick fixes” of e-mails, new checklists, bulletins often fail to address the fundamental systems factors which create the situation and rather than help they result in an ever more complex system. One could argue that as a whole they achieve exactly the opposite effect that was intended. Instead of making our system safer, our people are drowning in a huge heap of paper which is often conflicting with reality or with each other.

From a risk perspective, these “fixes” become paper defenses, not only are they useless, but potentially worse than useless because they give us a false sense of security. In theory one can make a risk assessment and claim that with these new defences the risk is lower, in reality people are quickly drifting apart from this work as imagined.

This reason why it happens is understandable, our managers are always fighting the proverbial operational fires and have little time to sit back and consider the problem from a distance.

This is where the SMS and the safety manager can do the biggest service to the organisation, they DO have time to think at a systems level, understand all the different local rationalities of the people involved and build a systems level picture about the safety problem.

A systems viewpoint means seeing the system as a purposeful whole – as holistic, and not simply as a collection of parts.

From Skybrary:Improving system performance – both safety and productivity – therefore means acting on the system, as opposed to ‘managing the people’. Safety must be considered in the context of the overall system, not isolated individuals, parts, events or outcomes. Most problems and most possibilities for improvement belong to the system. Seek to understand the system holistically, and consider interactions between elements of the system

To optimise a complex system we have to look at how the different elements are interacting and how we can improve those interactions. Not only is this good for safety, it also improves our whole systems function. Sometimes reducing obsolete defences that only work on paper, to “real” defences that are credible and have a better chance of being used by the people that are supposed to use them.

Ultimately this can lead to a shift in thinking about safety, from the so called Safety I: avoiding that things t go wrong to Safety II: Ensuring that things go right. It is again a concept proposed by Erik Hollnagel and is described here

The distinction might seem trivial, but can be profound. By focussing on the factors that make our organisation and the people in it work better, more often creating a successful outcome, we can increase overall performance of the organisation. In this new way of looking at safety, we can consider our people are actually as a solution, rather than a problem to be managed. But this is only possible if we understand human performance issues at a systems level. If we allow ourselves to be tempted by a “quick and dirty” Systems 1 borne explanation of failure in our system, we miss the opportunity to improve that system.

One very basic approach to the coaching process is the CRA technique. In many cases organisations tend to jump straight from a perceived problem to problem solving, creating actions before the problem and goals they want to achieve are fully understood.

In broad lines there are 3 distinct phases in the coaching process;

Consciousness:

Creating of consciousness about the safety issue by the management team and what fundamental goal they want to improve.

Defining the right problem to solve is often more important than going straight to the action phase. Also very important to measure afterwards if the actions actually were effective to achieve the desired outcome!

Responsibility:

Rather than assigning the first person that does not look to busy as the “victim” to deal with the issue, it is important to establish who is really responsible for implementing the solution. Unless that person takes responsibility (i.e. “appointed volunteer”, chances of effective implementation are slim to none. Does the responsible person have the authority and resources to deal with the problem? Else it needs to be escalated to a higher level. E.g. the CEO, can still delegate the task, but remains responsible for follow up of effective implementation.

Action plan:

Only after the 2 first steps will an effective, credible action plan be possible. Rather than telling the responsible person what to do, which rarely works anyway. The Safety Manager/coach facilitates an action plan, i.e. the responsible person comes up with possible solutions that they will implement which will achieve the goal. An action someone has defined himself is more likely to be executed with attention and enthusiasm. A top down “order” gets tacked on to a long to-do list and usually does not get done properly.

Important to note is that the Safety Manager/coach is not directing the manager to take any decision (the Safety Manager does not have that authority anyway).

The manager decides the appropriate course of action from their own understanding of the problem which the coach helped to clarify with the risk assessment and the safety investigation recommendations to clarify the options.

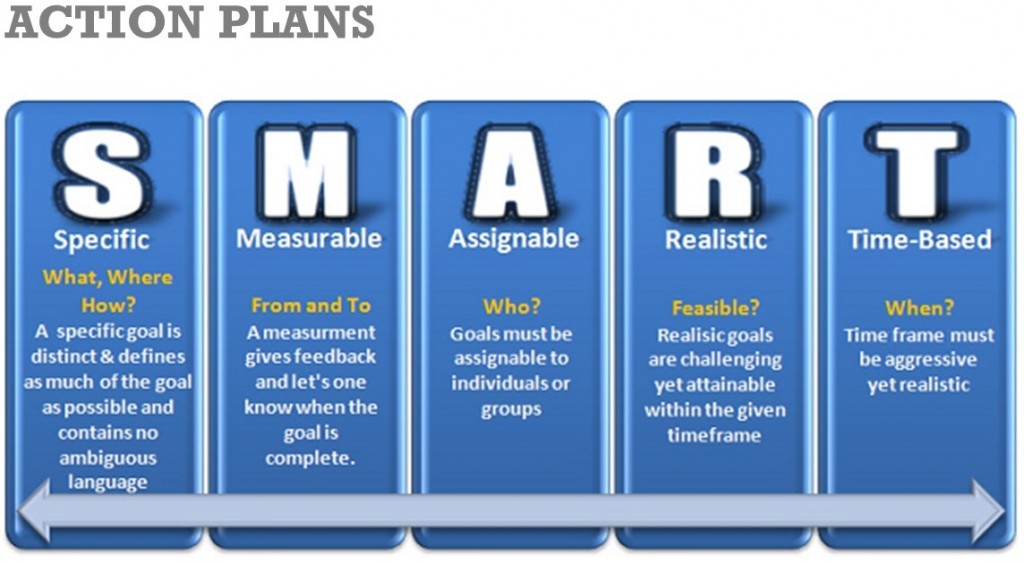

This increases individual confidence, motivation and ultimately successful implementation. Of course the follow up is very important too! “How do you know it works?” metrics for success can be defined already in this process and of course the SMART criteria are helpful to make the action plan concrete and easy to follow up.

I hope this presentation gave you some fresh ideas on how to better use your SMS as a tool to reduce risk in your organisation. I am more than happy at any time to have a chat and talk about your specific situation.

I hope this presentation gave you some fresh ideas on how to better use your SMS as a tool to reduce risk in your organisation. I am more than happy at any time to have a chat and talk about your specific situation.

You can reach me via

Email : Jan@SRMcoach.eu

Mob : +34601093969

Skype : Janelviajero

About the Author

Jan Peeters

Jan is an experienced Safety practitioner who is always on the lookout to improve SMS and the management of safety. He coaches organisations and individuals in Safety Management.

One Response to Complexity and decision making: Is SMS enough? [EBASCON 2017]

Leave a Reply Cancel reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.

MORE THINKING MATERIAL TO YOUR E-MAIL

RECENT POSTS

- Why do Safety Management Systems fail? 2018-05-16

- Our (mis)understanding of complexity in Safety: it´s not complicated it´s complex! 2017-11-19

- Complexity and decision making: Is SMS enough? [EBASCON 2017] 2017-02-28

- Is SMS enough? Complexity thinking and taking action… 2016-12-19

- How effective are our efforts to manage fatigue risk in aviation maintenance? 2016-06-28

CATEGORIES

- RISK MANAGEMENT (3)

- S/R/M BLOG (9)

- SAFETY ANALYSIS (1)

- SAFETY MANAGEMENT (9)

- Safety Manager (3)

- SAFETY MANAGEMENT SYSTEMS (4)

[…] Last year I spoke at the excellent safety event organised by Líder Aviação in Rio de Janeiro. My question was “Is SMS enough to make our organisations safer?” [Update, I gave a similar talk at EBASCON 2017 in Munich and I made a more elaborate resource page which details more explanation and links here] […]